Almost $37 billion in federal crop insurance payments went to a small number of insurance companies and agents, a new EWG analysis finds. And the House-passed GOP budget bill and the bill proposed by the Senate could send even more money their way.

The bill would hike those payments in part by slashing billions in food assistance funds, harming millions of hungry people to benefit wealthy companies and relatively few agents.

The Department of Agriculture’s Crop Insurance Program already pays billions of dollars every year to farmers experiencing reductions in crop yield or revenue. Taxpayers fund much of this.

But the program also pays billions each year to companies and insurance agents, EWG’s analysis finds. Between 2014 and 2023, the program paid out a total of $36.4 billion to agents and the 12 companies that the USDA allows to sell and service crop insurance policies, called Approved Insurance Providers.

Over the ten-year period, a little less than half of the total payments were made to companies and agents for “administrative and operating costs.” These cover costs like adjusting crop insurance claims and selling and marketing the policies. Agents get administrative and operating payments based on a percentage of the premium of every policy that they sell, but the companies can also choose to give them additional money, within statutory boundaries.

The remaining portion of the payments came from underwriting gains – the amount of money leftover from taxpayer- and farmer-paid premiums when yearly losses are smaller than premiums. Although these gains are nominally not guaranteed, the government’s agreement with companies ensures a rate of return high above other insurance industries.

In the last 23 years, there were only two years when the crop insurance companies did not have underwriting gains.

Eight of the 12 crop insurance companies are owned by publicly traded corporations, six of which are headquartered outside of the U.S., in places like Switzerland and Japan. These corporations are huge firms with large assets and astronomical CEO salaries.

So taxpayers – with a median household income of only $80,610 in 2023 – and to a smaller extent farmers, are giving billions of dollars every year to wealthy corporations that do not need handouts.

Companies gain at taxpayers’ expense

Taxpayers have heavily subsidized the Crop Insurance Program for decades. They provide 63% of total premiums each year, on average, with farmers paying for the rest of their insurance premiums.

Instead of the USDA solely running its own program, like it does with farm subsidy and federal conservation programs, the agency relies on private companies to service crop insurance policies. The program has a unique “public–private partnership” that sends taxpayer money to companies. The companies then give some of the money to agents who sell policies and complete insurance adjustments.

While supporters of the Crop Insurance Program say it benefits farmers, a significant portion of the money pads the pockets of companies and agents.

EWG analyzed data from the USDA’s Risk Management Agency to find the total compensation to crop insurance companies and agents for the 10 years between 2014 and 2023.

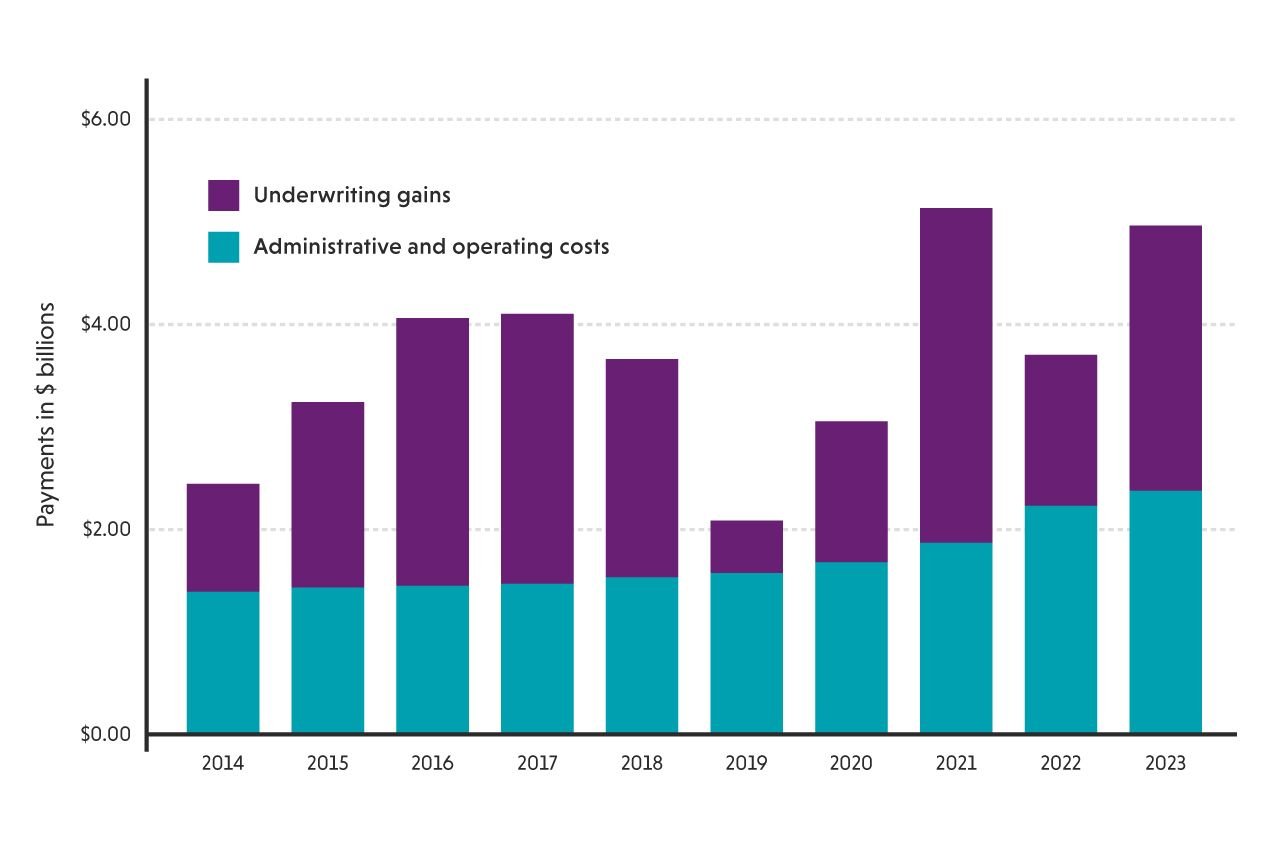

The total was $36.4 billion, with just under half of the money – 47% – being paid out for administrative and operating payments, while 53% was for underwriting gains. (See Figure 1).

Figure 1. Underwriting gains were slightly higher than administrative and operating costs between 2014 and 2023.

Source: EWG, from USDA Risk Management Agency, Crop Year Government Cost of Federal Crop Insurance Program.

Both underwriting gains and administrative and operating costs went up between 2014 and 2023. The highest ever total payments to companies and agents were made in 2021 at $5.13 billion, and 2023 had the second highest total payments of $4.96 billion.

Payments sent to companies and agents are a major portion of total program spending. Over these 10 years, total payments to farmers through premium subsidies fluctuated between $5.8 billion and $11.6 billion annually, while total compensation to companies and agents totaled between $2 billion and $5.1 billion a year.

In some years, over one-third of crop insurance program costs went to companies and agents, not farmers. For instance, in 2016, crop insurance premium subsidies for farmers were $5.87 billion, while total compensation to insurance companies and agents was $4.06 billion.

Mega corporations reap benefits

Extremely wealthy global corporations that own insurance companies are raking in billions from the Crop Insurance Program.

While payments have increased over time, the number of companies is decreasing, so fewer companies are receiving even more money. There are now just 12 crop insurance companies, compared to 14 in EWG’s 2023 analysis, and 17 in EWG’s 2015 report.

Of the 12 crop insurance companies, eight are owned by publicly traded companies. These are high-revenue global corporations, each with a net worth of at least $4.59 billion and as high as $119.3 billion, as of early June 2025.

The eight companies also had net incomes between $79.2 million and $9.03 billion in 2023. Annual compensation to each parent company’s CEO ranged from $630,000 to $27.9 million. Total annual CEO compensation across the eight corporations was over $69.6 million.

Six of these parent companies are headquartered outside the U.S., in Australia, Canada, Japan and Switzerland. EWG analyzed annual reports and proxy statements of the eight publicly traded corporations to find this information.

Of all 12 companies, only two are not owned by a parent company: Farmers Mutual Hail Insurance Company of Iowa and Precision Risk Management, LLC. One other crop insurance company, Country Mutual Insurance Company, is owned by a large private parent company, Country Financial. Because these companies are not publicly traded, little is known about them.

The other crop insurance provider, American Farm Bureau Insurance Services, Inc., is owned by the American Farm Bureau Federation. It’s a nonprofit organization that lobbies for the subsidies that guarantee the profitability of crop insurance companies.

See the map below for the U.S. locations of the 12 firms that sell crop insurance policies, along with the public or private status of their parent companies.

U.S. office locations of the 12 firms that sell federal Crop Insurance Program policies

A 2023 Government Accountability Office report showed just how high payments to crop insurance companies and agents have been, and that they will get more expensive in the future.

In 2022 alone, crop insurance companies earned commissions over $1 million per policy 14 times, covering some of America’s largest farms.

And the crop insurance companies received an average rate of return for their underwriting gains of 16.8% between 2011 and 2022. That's significantly higher than the 10.2% rate of return that would be expected in a market setting not controlled by the government.

The GAO also estimated that total payments to companies and agents would be $38.1 billion between 2024 and 2033, which would be over a third of the $101 billion total costs of the program.

Payments would soar under budget bill

But the GAO’s estimate of future payments would be even higher if the budget reconciliation bill were to pass and become law.

In addition to increasing crop insurance subsidies that would go to farmers, the bill would dramatically increase payments to crop insurance companies and agents.

The legislation would raise administrative and operating payments to keep up with inflation and make higher expenditures to companies that sell fruit and vegetable crop insurance policies. The bills would also provide the companies with an extra payment of 6% of crop insurance program premiums, resulting in millions of dollars in extra payments each year.

Part of this funding hike would be paid for by making massive cuts to funding for SNAP, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, along with cuts to Medicare and Medicaid.

Lawmakers should not cut desperately needed food assistance and healthcare to help finance more payouts to corporations and insurance agents. Increasing these payments at the expense of hungry people would cause serious harm to millions while only benefiting wealthy companies and relatively few agents.

Crop insurance companies, including those owned by already-wealthy mega corporations, currently receive billions of dollars each year from taxpayers and farmers. They do not need even larger payouts.